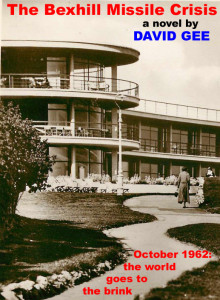

Extract from THE BEXHILL MISSILE CRISIS

MONDAY

‘There can be little doubt that something is going on.’

THE TIMES, 22 October 1962,

reporting on US tension over Cuba

In Washington the Cuban ‘situation’ of which the world at large was only today becoming faintly and uneasily aware, had entered its second week.

It was eight days since the discovery by U-2 reconnaissance planes that, ninety miles from Florida, the former hosts of pirates and mobster casino operators were now entertaining Soviet technicians and nuclear missiles with a strike capability against most of the American continent, from Hudson’s Bay to the capital of Peru.

For Washington’s political and military leaders it had been a week of nerve-wracking debate in the Pentagon, in the State Department and in the Cabinet Room at the White House.

For the unwitting average American citizen a week of lively wrangling over the forthcoming Congressional elections.

For the people of Great Britain a week of prurient speculation about a homosexual Admiralty clerk named William Vassall, on trial at the Old Bailey for offences under the Official Secrets Act.

For fifteen good ladies in the Borough of Bexhill on the Sussex coast a week of fastidious (‘pernickety’, a bank manager’s wife complained to her friend Lillian Rutherford in Hastings) planning for next Saturday’s bazaar in aid of Moral Re-Armament.

* * *

Monday October 22nd 1962, the eighth day of the Cuban Missile Crisis, was a tense and hectic one for the staff at the White House, the Pentagon and the State Department as they prepared for the President’s declaration on national television and radio, at 1900 hours, of the naval ‘quarantine’ of the ill-starred island.

* * *

In North London’s Hampstead Garden Suburb, Evelyn Hunter, wife of a Bond Street jeweller, pressed clothes and packed her husband’s suitcase; he was flying to Amsterdam on Tuesday to stock up on diamonds.

She also ironed and packed for her own five-day trip to Bexhill with Andrew Rutherford, whose business partner was a friend of the Hunters from Sidney’s days as a buyer in Selfridges. They were to stay as guests of a divorced friend of Andrew’s.

When a 36-year-old married woman is about to spend five days in the country with an unmarried younger man, the question of what she should wear – even when the unmarried younger man is not her lover – assumes more than its usual importance. Evelyn took care to select from her wardrobe sober dresses and cardigans in which she could be confident that her host and his daughter and the virtuous citizens of Bexhill would accept her as a grass widow and not write her off as a society tart.

A sense of unease hung over her all day.

‘You’re very edgy tonight,’ her husband observed at the end of dinner, which they had eaten in near-silence.

‘I’m always edgy when you go off on these trips,’ she said, aware that her unease had more to do with her impending visit to Bexhill than with Sidney’s third trip of the year to Holland. ‘I still I wish I was coming with you.’

‘We’ve been through all this before,’ he reminded her. ‘You’d only end up bored to death in the hotel.’

‘I could wander around Amsterdam while you meet your dealers.’

They had been through this before. Sidney gave a loud sigh. ‘You’re going to Bexhill,’ he said. ‘I’m sure you and Andrew will have a nice time at his friend’s house.’

Sidney Hunter had no qualms about his wife going away with Andrew. On Sidney’s Masonic nights Andrew sometimes took Evelyn out for dinner or a show. Sidney was sure – as was Evelyn – that Andrew entertained no plans to compromise her. They had not failed to notice that the average age of the ‘fillies’ in his ever-changing stable was not much more than half of hers.

‘I suppose we will,’ she forced herself to concede. She leaned across to take his dessert plate and stacked it with hers.

‘The change of air will do you good. And some younger company.’

Evelyn had started to rise. Now she sat down again, taken aback by this line of conversation. ‘Why should I need some younger company all of a sudden?’

‘Well – I’m such an old fuddy-duddy. You must sometimes wish you had someone a bit more exciting in your life.’

The dessert plates rattled as Evelyn let them drop back onto her tablemat. ‘Don’t you dare say that. I’ve never regretted choosing you and don’t you ever think otherwise.’

‘All right, lovie. I’m sorry.’ He rose and moved round the dining table to kiss her cheek. She patted his head, ruffling the thin hair. Then he went to turn on the television in the living half of the room while she took the dishes out to the kitchen, wondering if – and if so, why – he shared her apprehensions about the visit to Bexhill.

* * *

Andrew Rutherford left his packing for Tuesday morning. He spent a normal busy Monday at his company’s offices in Mayfair, a display and artwork agency established, with Sidney Hunter’s backing, eighteen months ago which now employed a staff of four and provided Sidney with a good return on his investment.

After work he had a drink in a local pub with his agency partner Algernon Farley – ‘Algie’ – who was fifty-five to Andrew’s twenty-four. At 6.15 he met his nineteen-year-old girlfriend Fiona – Lady Fiona Camelford-Jones – outside Swan & Edgar’s and took her to dine at Quaglino’s. After dinner they went back to Andrew’s penthouse flat inSouth Kensington where Fiona duly sang for the supper he’d given her.

‘Will your friend Mrs Hunter be getting some of this while you’re in Sussex?’ she asked as she began dressing. Even stepping into coral-pink knickers, Lady Fiona managed to look ladylike. In September she had accompanied Andrew to a cocktail party in Hampstead Garden Suburb. Fiona thought – and said – that the Hunters and their neighbours were sub-urban (a geographical fact) and Jewish (which was only true of five of the fourteen guests). Whatever opinion the Hunters formed of Fiona, they kept it to themselves, as did Lillian, Andrew’s mother, when she was introduced over a restaurant dinner in Knightsbridge.

‘Mrs Hunter’s not that sort of friend,’ he replied, lying in a black silk dressing gown on top of the bedclothes.

‘I think she’d like to be.’ She fastened her suspender belt.

‘Older woman, younger man. Bit Somerset Maugham, wouldn’t you say?’

Perching on the edge of the bed she drew on the first of her stockings. ‘My parents tell me I sat on his lap once as a baby, when they were in Malaya.’ She snapped on the stocking. ‘Did you know he was a queer?’

‘Yes, I did.’ He reached for a cigarette as she pulled up the other stocking.

‘You’re like a character out of Maugham, Andrew. A bit dated. Always striking poses. Madly in love with yourself.’

On these criteria Noël Coward would be a more apt comparison, Andrew thought, but he kept this to himself. Instead he asked: ‘What’s brought this on? Are you peeved that I’m going to Bexhill with Mrs Hunter? Or did my performance tonight fail to bring satisfaction?’

‘I couldn’t care less who you go away with – to Bexhill or anywhere else.’ Her brassiere lay on the floor and she bent down to pick it up. ‘But since you ask, Jocelyn and I are agreed that you’re only a four-star performer.’

He grimaced. ‘I know you two were in school together, but I hadn’t realized that you compare notes over a scorecard.’

‘Ever since Roedean.’ Her fingers briskly buttoned a white nylon blouse. White on white. Fiona never sunbathed; her skin was porcelain, but not flawless: knees and shins bore indentations from school hockey injuries. Andrew’s skin had the look of tan leather; he’d spent the first ten days of October in Positano. ‘Of course it was girls then.’

‘And I only rate four stars? I’m crushed.’

She wriggled into a knee-length navy-blue skirt, her uniform as a sales girl in Harrods (debt and divorce, post-Malaya, had lowered the Camelford-Jones standard of living). ‘We give three to a man who takes very good care of himself and four to a man who takes very good care of us.’

‘And five to the one who does both, I presume?’

‘Right.’ she said, splashing her neck from one of his bottles of aftershave. ‘But it takes a real man to do that.’

‘Which, in the view of this tribunal, I am not.’

‘You try a little too hard to please.’ She returned to the bed and bent over to kiss his forehead. ‘Next time think of yourself a bit more. Not too much, of course. We wouldn’t want you to turn into a rugby-player.’ She left the bedroom with a cavalier wave. Moments later he heard the front door click shut.

Lying on the white silk bedspread in his black silk robe, Andrew frowned. If he had to put a name to his image of himself, it would be ‘Byronic’. ‘Maughamish’ definitely wouldn’t do. If he were to discuss Fiona’s rating system with Algie (who was what Fiona called ‘a queer’), Algie would purse his lips and say something like: ‘You’ll have to butch yourself up a bit, darling.’

‘Butch’ wasn’t Andrew’s style – any more than it had been Byron’s. Byron must have had many girls like Fiona in his life. And, quite possibly, a friend like Algie.

* * *

Evelyn closed her library book in the middle of a chapter, unable to concentrate. She fought down the desire for a cigarette. Only a light smoker himself, Sidney hated her to smoke in bed and was grumpy if he woke in the morning with the smell of tobacco in the room. Tonight he’d taken one of Evelyn’s sleeping pills to calm the nervousness he always felt before flying. Now he snored asthmatically on his stomach beside her.

The bald patch at the back of his head shone in the lamplight, a droll symbol of the durability of their union. When Evelyn had first known him in 1945, thirty-two to her nineteen, he’d had a full head of hair which had barely begun to recede by the time of their wedding two years later.

You must sometimes wish you had someone a bit more exciting in your life, she repeated to herself and immediately – ridiculously – remembered the thirty-year-old German who’d clumsily courted her in a Torquay hotel two years ago (Sidney in Holland again). In the lamplight Evelyn looked again at her 49-year-old husband’s balding pate and pictured in its place the German’s head with its thick black mane. If – she’d managed to forget his name – were here now, at eleven forty-something, would he be snoring into the pillow, or would his blunt fingers be probing her parted thighs while she arched her breasts into his face, sighing and moaning?

She sighed a different sigh from the one in her mind. She hadn’t married for excitement fifteen years ago, she’d married for comfort and security, and comfort and security was what she had got. It was too late, now, for excitement, too late for passion, too late for ecstasy.

Evelyn turned out the light and slithered down into the bed. She wrapped one arm round her husband’s body, embracing the familiar warmth of his flabby stomach, and tried to sleep.

* * *

Afterwards, when it was all over, Evelyn would convince herself that her unease, the ‘edginess’ her husband had noticed, had been a premonition of the Crisis that was about to break – the global one in Cuba and her personal crisis in Bexhill.

* * *

In London it was almost midnight. In Washington it was approaching seven p.m.

At the State Department a group of ambassadors from America’s allies, shocked and shaken after a briefing by Under-Secretary George Ball, was gathering in front of a television set for the President’s speech. As they waited a savings and loan company’s commercial appeared on the screen, earnestly demanding of the unseen and unforeseeing audience:

‘How much security does your family have?’

A ripple of laughter momentarily exploded the tension in the briefing room. Then, as the picture gave way to the seal of office of the President of the United States, the group of men seemed to draw breath together.

* * * * * * *